CALGARY -- Calgary police are investigating a man who died four months ago for numerous sex assaults, including at least one that dates back decades.

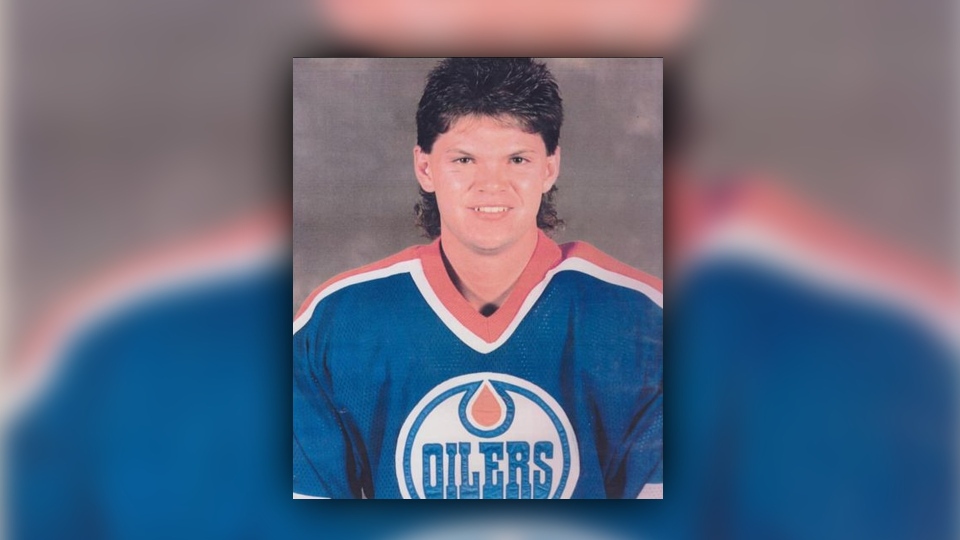

CTV News has learned the alleged incidents range from the 1990s to as recently as last year and are alleged to involve Timothy Edward Flanagan.

- Warning, details in this story may be upsetting to some readers

Flanagan — who was well-known in Calgary’s energy sector and was drafted by the LA Kings in 1985 before his hockey career ended — died by suicide at the end of September.

His death came six days after police executed a search warrant at the 53-year-old’s southwest Calgary home on Sept. 22, 2020.

Court documents related to the case are sealed, meaning it’s not known what police seized from the home or even what exactly they were looking for. Sources say a computer was taken to be analyzed for photos.

Police are also sharing few details about their investigation due to Alberta’s privacy laws, including what led officers to search Flanagan’s home.

But that’s where at least one assault is alleged to have taken place.

Neighbours say a woman fled Flanagan’s home with no clothes on in search of help not long before his Sept. 28, 2020 suicide.

RCMP say they were called to investigate his death just outside of Calgary.

Police wouldn't say how many women have come forward, however one woman who reported her case to police did speak with CTV.

'Didn't give me that vibe at first'

CTV has agreed to protect the woman's identity because she is a sexual assault complainant. We are referring to her as Michelle for the purposes of this story.

Michelle says she met Flanagan at a bar in the mid 1990s. He gave her his phone number and she says she agreed later to go out with him for a drink.

“I don't think I would have gone anywhere with somebody that I felt uncomfortable with," she said.

"He didn't give me that vibe at first. Afterwards it got totally scary.”

Michelle claims Flanagan drugged her, bound her wrists and sexually assaulted her repeatedly throughout the night, along with photographing her.

"I was terrified. He just kept taking pictures and touched me and it was almost like he was setting me up trying to get certain types of photos," she said.

After years of staying silent, fearing potential repercussions, Michelle worked up the courage to file a police report last March. Months later, she got a call from CPS.

“When I spoke with the detective he told me that there were potentially more victims,” she said, adding that police told her, “When they did pick him up they seized photos or videos, he was on dating sites, I remember seeing him on Plenty of Fish.”

She says she learned about his suicide from police.

“At this point there’s no accountability," she said. "He’s not accountable for anything because he’s gone.”

The Criminal Code of Canada prevents a prosecution against a dead person.

“Once an individual has passed away there is no real criminal matter that can be taken up,” said Doug King, a Mount Royal University criminologist.

“The key reality is that all people who are accused of a criminal offence, either charged or suspected of it, are afforded the right to defend themselves and if the person can’t defend themselves the courts won’t proceed any further with it.”

Case isn't closed

Calgary Police say when a suspect passes away before an investigation is concluded, it’s standard to ‘finish examining all the evidence to try to learn what happened’ to ‘give some closure to victims’ and to rule out other potential suspects.

"Our service has officers dedicated to reviewing old sex crime and homicide cases to see if new technologies, information or DNA records can move the investigations forward," reads a statement from Calgary police.

Toronto Police recently used DNA to solve the high-profile 1984 rape and murder of nine-year-old Christine Jessop.

The killer in that case, Calvin Hoover, had died years before last fall’s announcement that confirmed he was responsible.

And the rationale for releasing his name in that case was clear, according to experts.

“What we know about recidivism rates among violent sex offenders, in particular child sex offenders and sexual murders, is that they reoffend frequently and he’s likely to have other victims,” said Michael Arntfield, a former police officer and professor at Western University.

Flanagan's life and death remain a mystery to those who knew him. That includes Premier Jason Kenney, who attended Flanagan's memorial service and spoke openly about his suicide, attributing it to the poor economy.

Upon learning of the CTV investigation, the premier’s office said Kenney only went to high school with Flanagan and was unaware of the allegations against him.

Why it can take victims time to come forward

It has taken Michelle decades to work through the different emotions associated with the night she went out with Flanagan.

Shame, guilt, sadness and anger are just a few.

“I felt like it was my fault," she said. "Different things trigger you, I don’t look at things the same as before that happened, happy go lucky, laughing. It takes a part of your soul.”

It is not uncommon for victims of sexual assault to take years to file a police report, if at all.

“It’s really important to remember that being sexually assaulted is a traumatic experience,” said Deinera Exner-Cortens, an assistant professor at the University of Calgary.

“It can take time for someone to reconstruct what’s happened to them, if they had been drugged by their perpetrator or they were under the influence at the time that can make things really confusing.”

Some common reasons for not reporting include, shame, denial, fearing consequences, and not being believed.

“When we’re asking, why didn’t she come forward, we’re putting the onus on the victim for what’s happened to them,” said Exner-Cortens.

“It’s important to ask, why did he do this and what can we do as a society to prevent this from happening?”

Michelle can never get back what she says Flanagan took from her, nor will she get her day in court.

She is, however, finding some closure in sharing her story and letting other potential victims know they aren’t alone.

In a statement, Calgary police say there’s no statute of limitations on criminal sexual offences in Canada and, "we encourage anyone who has been a victim of a serious crime to report it, even if many years have passed since the incident."

Michelle finds other comfort in this case.

“He’s dead now he can't hurt you," she said. "If you want to come forward and tell your story, you have that right.”

Victims of sexual assault can contact Calgary Communities Against Sexual Abuse at 1-866-403-8000.