LETHBRIDGE -- Researchers at the University of Lethbridge are developing new testing equipment that will pave the way for exploring deep outer space, and possibly future moon landings.

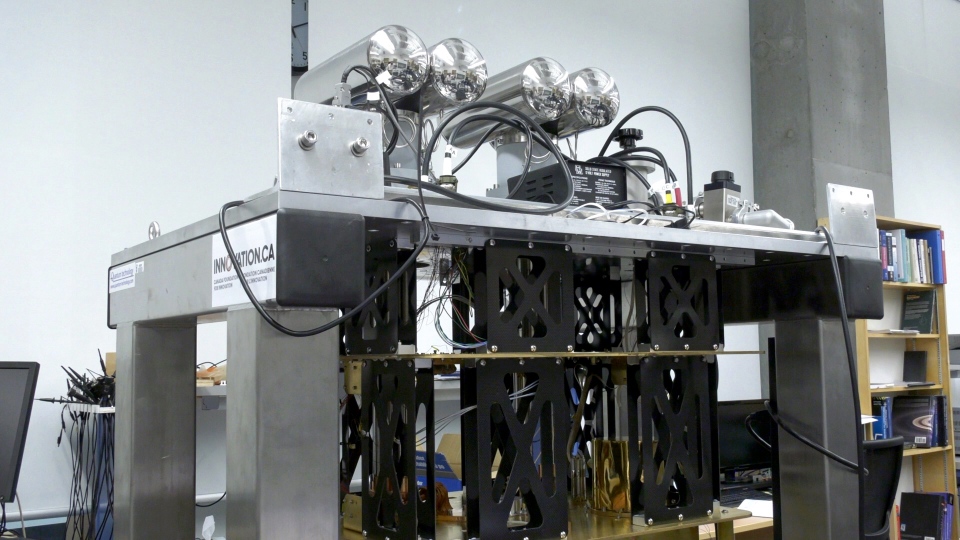

The Astronomical Instrumentation Group at the University of Lethbridge has received funding to build a large facility cryostat that would be able to evaluate the performance of instruments destined for space exploration.

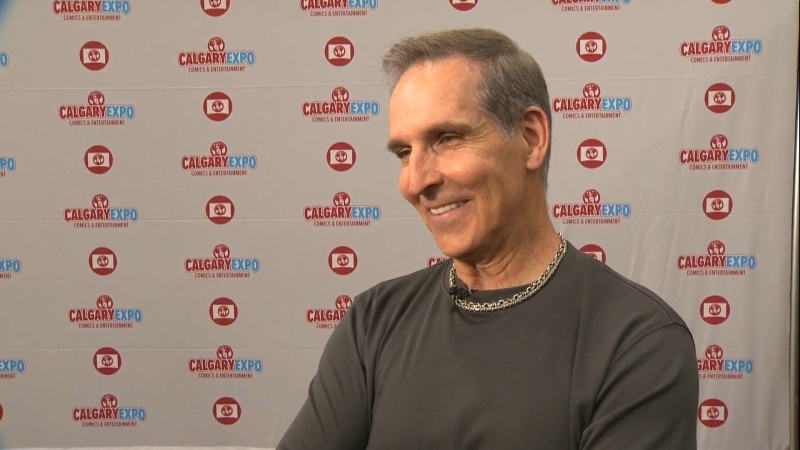

“In simple words, you need a need a very large freezer, an extremely large freezer, and an extremely cold freezer,” said Dr. David Naylor, leader of the AIG group.

The U of L already has a smaller unit that will test how instruments function in extreme cold.

Naylor said it will generate temperatures 10 times colder than the coldest known part of the universe.

The new chamber will be 2.5 times larger and will be used to develop and test the world’s first cryogenic far-infrared, post-dispersed polarizing Fourier transform spectrometer.

The new type of spectrometer has been identified by leading space agencies as a necessary next step to explore galaxy evolution and planet formation.

The spectrometer and other instruments will be sent into space as part of the SPICA Mission, a joint project led by the European and Japanese Space Agencies. Canada is also involved and the Canadian effort is led from the U of L.

“Space exploration is extremely risky,” said Naylor, adding the only way to mitigate that risk is through repeated testing.

“When you launch something into space, there is a decade of work, testing the instrument in the realistic environment you have in space.”

Naylor said while he is proud of the work being done for the SPICA Mission, the new testing facility will also be large enough to test any instruments that will be used in future lunar missions.

“The moon is actually a much harsher environment than Mars,” he said.

“It takes the moon 28 days to orbit the earth, so it is night on the moon for roughly 14 days. So it gets extremely cold, -250 C cold.”

Any instruments or equipment being sent to the lunar surface has to be able to function under those harsh conditions.

“In a nutshell, nothing works at those temperatures. Electrically, optically, thermally, mechanically, everything, the physics of material properties changes abruptly when you get to low temperatures and it becomes, really, a challenge.”

Canada is a founding member of the International Lunar Gateway Project, which is intended to serve as a solar-powered communication hub, science laboratory, short-term habitation module, as well as a holding area for rovers and other robots that will be used in lunar research.

Canada’s commitment to the project means that a Canadian could someday set foot on the moon.

“And those boots will belong to kids at Mike Mountain Horse, or children in that age group, somewhere across Canada who will be the first to plant the Maple Leaf on the moon," said Naylor.

But with a projected launch date of 2032, that achievement is still years away, and Naylor expects he will be long retired by then.

Still, he maintains the U of L role in testing the instruments for future space exploration is something to be proud of.

“Any hardware, regardless of its type or application, must be proven to survive lunar night with limited resources,” said Naylor.

“The LFC will be a unique facility in Canada, and one of only a few in the world capable of simulating the hostile environment of the coldest parts of the lunar surface.”

The total value of the project is $860,000. Funding has come from a variety of sources, including a $250,000 grant from the Canada Foundation for Innovation.

Another $360,000 has been secured from four industrial partners, all active in the space exploration sector: ABB (Quebec City, Quebec), Blue Sky Spectroscopy (Lethbridge), QMC Instruments (Cardiff, UK) and the Space Research Organization of the Netherlands (Groningen, the Netherlands).

The research team will apply for matching funds from the Alberta government later this year.