Breathe easy: How an air quality forecast comes together

A stock photo of Calgary's skyline. (Getty Images)

A stock photo of Calgary's skyline. (Getty Images)

Last August, I agonized about whether or not my twins would get their second birthday party at Calaway Park, or if it would be an indoor day.

On this particular morning, the Air Quality Health Index sat at a two. That's good. Ideal air quality for outdoor activities. The remainder of the day, however, told a different story; the expectation that afternoon was a seven. That's high-risk, where vulnerable populations (such as fresh two-year-olds) are advised to stay indoors.

I checked the forecast: Environment and Climate Change Canada has the Firework model, and BlueSky Canada has the FireSmoke model. One showed smoke rolling through that day; the other showed it passing nearby. What's a forecaster to do?

This story has a happy ending – we went. It remained overcast, some of which was indeed smoke. We did not, however, have any haze on our parade. The entire day went just as well. We played outside when we got home. The smoke never reached the surface, and our air quality never fell to a seven.

So what happened?

"[The Air Quality Health Index] AQHI measures acute risk of bad health outcomes – it's based on a three-hour exposure period.," explained Paul Makar, a senior research scientist with Environment Canada and Climate Change's air quality modeling and integration unit.

"So over a full day, scientists will have eight AQHI values to work with."

Makar says that it's not catastrophizing; it's taking the available information, submitting it to forecasters, and allowing them to make the most educated guess at their disposal. "What we're trying to do in this case is say 'given what we've got, how bad can it possibly get?'"

There are three components which can change our AQHI value:

- Ground-level Ozone (O3) is mostly specific to the summer months. It's the driver of smog.

- Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) is released by vehicle emissions and fossil fuel power plants and can be held to the surface in certain conditions within the planetary boundary layer (where we live).

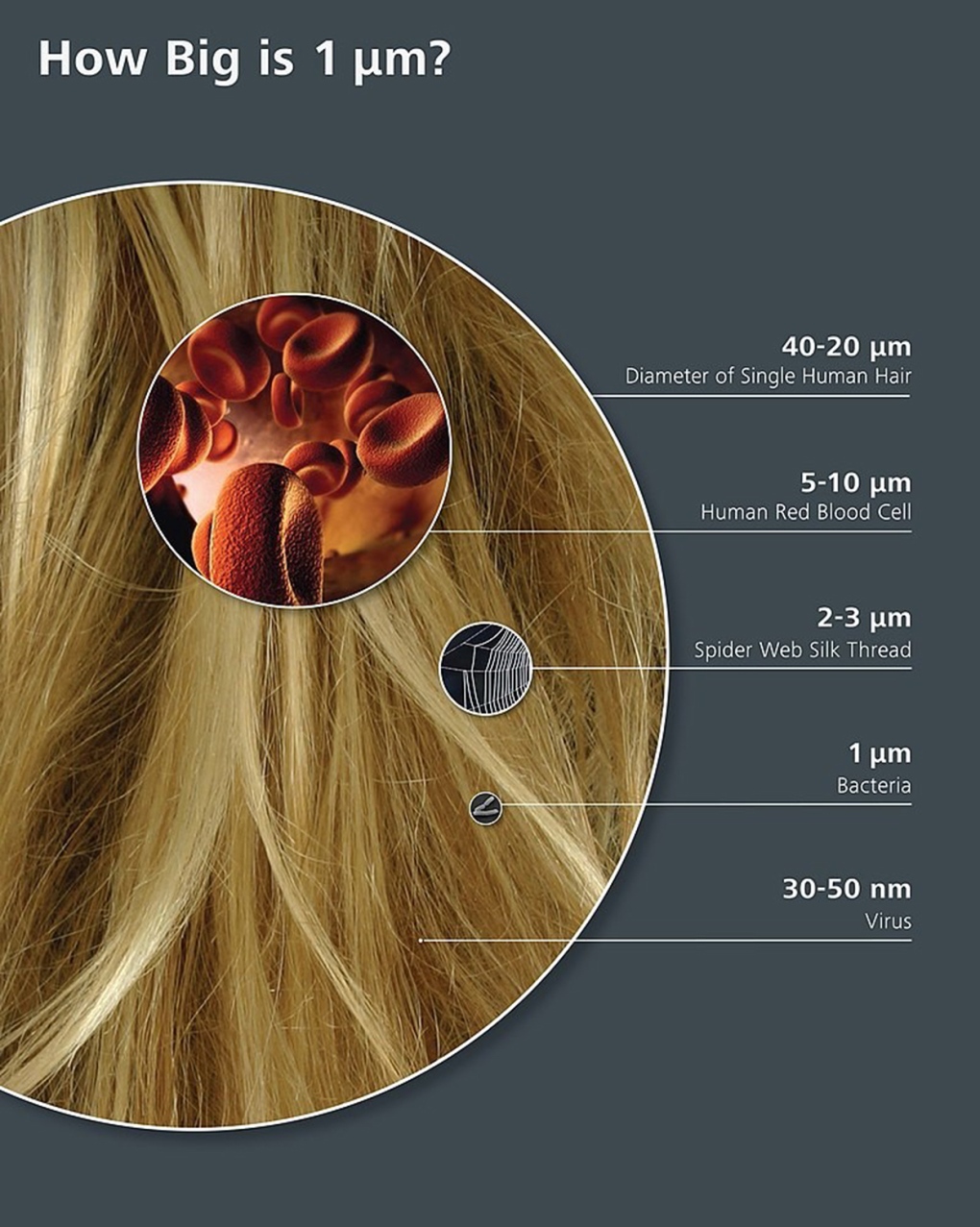

- PM2.5 is a mixture of vehicle emissions, industrial facilities, or natural sources, like wildfire smoke. It stands for Particulate Matter of 2.5 microns (μm) or less. The chart below offers comparisons.

How big is 1 micrometer? (image courtesy: ZEISS Microscopy from Germany - How big is 1 micrometer?, CC BY-SA 2.0)

How big is 1 micrometer? (image courtesy: ZEISS Microscopy from Germany - How big is 1 micrometer?, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Putting a forecast together for smoke requires a large team of spectacular scientists. The volume of variables they're working with to make sense of smoke is staggering. I couldn't imagine the length of this formula that applies every imaginable condition to the model, nor the computing strength needed to turn it into a national forecast.

Jack Chen filled me in! He's a modeling scientist, part of the 34-person team tackling Environment and Climate Change Canada's smoke forecast operation.

"We are very good at it now, but what we have now is a state of science that gives us good numerical guidance for our air quality forecasters," explained Chen.

Smoke forecasting is another level of weather forecasting; the movement of air affects the position of the smoke and, according to Chen, there are "a whole lot of complex dispersion chemistry problems that need to be resolved to give us what we have now."

And that's just the atmosphere; the ground matters too! Different areas burn better. It's good they have help,

"We're seeing a long-term collaboration between Environment Canada, Canadian Forest Service, [and] measurement communities in the (United) States," said Chen."This is all driven from fundamental science, and in close collaboration over years in putting all this together.

"In order to get this stuff out in the forecast in enough time to be useful, we have to run it through one of the biggest supercomputers in the country."

A massive supercomputer amalgamates this information, applies it, and it can spit out a national forecast for Environment and Climate Change Canada's local meteorologists – and the public – to view and assess.

THE STATE OF THE SCIENCE – PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE

No forecast model ever gets it right 100 per cent of the time. This is science, math and computer engineering melded together. That can make for imperfections – it's a lot of moving parts. If there's an error on day one of a forecast, that can easily compound into further errors for days two and three. Paring it back to run-of-the-mill (or not!) weather, here's a pair of tweets from the big snowfall event of this April:

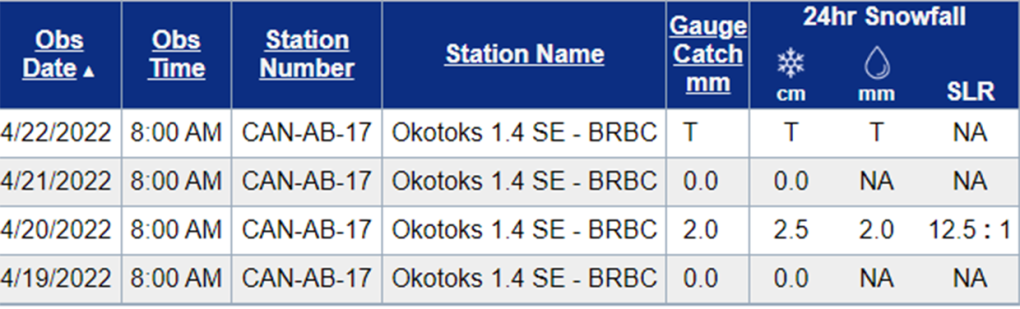

That day, we had over 30 centimetres of snow near the airport (thank you, Rolf!), while a station in Okotoks participating in CoCoRaHS (the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail & Snow Network) declared a meagre 2.5 centimetres.

CoCoRaHS chart of snow accumulation in Okotoks, Alta. for specific days in April 2022.

CoCoRaHS chart of snow accumulation in Okotoks, Alta. for specific days in April 2022.

In this instance, forecast models declared between two and 17 centimetres. It falls on scientists to make educated guesses, based on both available data and similar past events. Snow – and snowfall warnings, as was the case with this event in Calgary – are certainly something to take seriously. While smoke or air quality advisories lack the same impact on a commute, they, too, deserve healthy measure of respect.

So much so, that the scientific community has seen a funding increase in this regard.

"There are a lot of different agencies that are now realising the importance of all this," said Christopher Rodell, a PhD student in atmospheric sciences at UBC who also works with BlueSky Canada, which is a collaboration of forest fire information between Alberta and British Columbia. "There's a fair amount of funding that's coming into the system or the sciences now, which is really helpful for the model development work. Things are definitely evolving quite rapidly in that space."

BlueSky Canada also runs the FireSmoke model.

Development of FireSmoke began around 2013 and went online in 2016; from a scientific perspective, that’s relatively new. Advancements are in the works with the funding increase.

"We've got a couple of proposals now, one's called Inferno – we want to fly an instrumented aircraft into downwind forest fire smoke plumes… [And] we're using satellite data to estimate emissions and heights, the forest fire plumes in Canada and around the world,” explained Paul Makar.

Makar says it's more about collaboration than competition between organizations. Multiple research teams, along with a substantial number of grant recipient universities in the United States, continue to push this field forward.

They have to. Here's a look at a report from 2019, cataloguing the worst wildfire seasons in B.C. dating back to 1950:

This is not the sort of trend we want to be in, and yet, here we are: ClimateData.ca launched in 2019, to model the effects of climate change. Here's a peek at Calgary, for the curious.

The takeaway: wildfire frequency and intensity stand to increase in the future. "Bearing in mind that [Jack Chen and I] are climate modellers, the scientific consensus is that climate change will result in hotter conditions in the future… What causes fires? Drought, decreased snowfall, decreased rainfall. Those are conditions that will lead to forest fires... generating the large fires in particular, larger fires."

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

NEW Federal Liberals to pick new leader on March 9 as rules for leadership race are defined

The Liberal Party of Canada have announced leadership race rules late Thursday, including a significant increase in entrance fees and a requirement for voters to be Canadian citizens.

Liberals will remove 'fraudulent' memberships, as some register their pets to vote

A federal Liberal spokesman says the party can and will remove "fraudulent profiles" from its list of electors eligible to vote for its next leader.

NEW Why four Canadians traded their traditional office space for a life on the road

CTVNews.ca asked Canadians who've embraced the digital nomad lifestyle, or have done so in the past, to share their stories — the challenges, triumphs and everything in between.

New L.A.-area fire prompts more evacuations while over 10,000 structures lost to the 2 biggest blazes

The two biggest wildfires ravaging the Los Angeles area have burned at least 10,000 homes, buildings and other structures, officials said Thursday as they urged more people to heed evacuation orders after a new blaze ignited and quickly grew.

Is the Hollywood sign on fire?

As fires scorch Los Angeles, fake images and videos of a burning Hollywood sign have circulated on social media.

NEW Five ways homeowners can protect themselves from contractor fraud

Building or renovating a home can be one of the biggest expenses of one's life. It's costly, and potentially even more expensive if something goes wrong. Between 2022-24, the Better Business Bureau (BBB) received hundreds of complaints about general contractors in Canada.

How to improve climate predictions? McGill researchers turn to 19th century letters

A team led by McGill University researchers came up with a method they hope could improve climate models over Africa by combining them with 19th century missionary records, refashioning dubious documents in a bid to better inform projections of global warming's impact.

Ex-Trump adviser says Canada in 'difficult position' amid tariff threat, Trudeau resignation

In the face of a potential tariff war, U.S. president-elect Donald Trump's former national security adviser John Bolton says 'Canada is in a difficult position' in part due to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's resignation and a looming general election.

Canadian travellers now require an ETA to enter U.K. Here's what to know

Starting Jan. 8, Canadians visiting the U.K. for short trips will need to secure an Electronic Travel Authorization (ETA) before boarding their flight, according to regulations set out by the U.K. government.