Alberta's Air Quality, Part II: The Human Impact

Smoke rises from hotspot seen during an aerial tour of the Verdant Creek Wildfire, which is currently estimated to be 15,500 hectares, in Banff National Park, Alta., Tuesday, Aug. 22, 2017.THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jeff McIntosh

Smoke rises from hotspot seen during an aerial tour of the Verdant Creek Wildfire, which is currently estimated to be 15,500 hectares, in Banff National Park, Alta., Tuesday, Aug. 22, 2017.THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jeff McIntosh

"So, you turn this red dial here, and you'll hear a click," my doctor tells me. His eyes show a sympathetic smile beneath a medical mask.

I haven't used an inhaler in a long time. I'm still getting used to it. I'm meant to take it before hockey; I have exercise-induced asthma. It usually doesn't bother me, but the personal impact of 2021's smoke was jarring on my lung capacity whenever I participated in sports. So made a choice.

I'm surely not alone.

We're going to start by talking about monkeys. Rhesus macaque monkeys, to be specific.

Rhesus monkeys in Florida. (file)

Rhesus monkeys in Florida. (file)

In 2008, California experienced a series of wildfires that impacted a colony of these monkeys at a Northern California zoo. The best person to explain the study is Sarah Henderson, scientific director of environmental health services at the B.C. Centre for Disease Control. She's been studying smoke for nearly 20 years, dating back to an inciting incident: the British Columbia wildfires of 2003, which remains "one of the most catastrophic in British Columbia's recorded history." (Source: gov.bc.ca)

Okanagan Mountain Park forest fire seen from Peachland, B.C., Thursday, Aug. 21, 2003

Okanagan Mountain Park forest fire seen from Peachland, B.C., Thursday, Aug. 21, 2003

Here's the resulting research:

"[Infant] lungs never grew as big as infants who were not exposed, and their immune function was dysregulated throughout their lives, so they never had as strong an immunological response as unexposed infant monkeys," explained Henderson. "They've now studied the offspring of those monkeys. Their offspring also do not have as good immunological response as the offspring of the non-exposed monkey.

"So these indications that there's actually genetic changes associated with the smoke exposures that are passed on through generations."

If you'd like to read some of the abstracts, here's one from the California Resources Board, and another from the National Library of Medicine.

An important note: a fully-grown female rhesus monkey weighs 8.5 kilograms; males reach 11 kilograms. Their smaller size can make for greater impacts. Whether it's a minor asthma case, a major lung issue, a young child or a healthy adult, there's a lot to know, and it affects us all differently.

The key component of that last sentence: it affects us all.

THE WHAT AND THE WHY

In the previous article, we discussed the general makeup of PM2.5 particles.

Henderson spoke to the human impact. Because these particles are so small, and because we breathe them in, the lungs are where we feel the majority of the effect. Henderson says this is especially true for people with pre-existing lung conditions such as asthma or COPD (Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). "Anything that is restrictive, when the airways want to close up, fire smoke will trigger that, and they'll be the most affected."

She adds the body's response "can cause inflammation to the lungs, and that inflammation can spill over into the rest of the body. So inhaling wildfire smoke can actually affect your heart, it can affect your brain."

"We do see a higher incidence of things like heart attacks, strokes, out-of-hospital cardiac arrests — those really kind of severe acute health outcomes, they tend to occur more frequently when it's smoky outside."

25 of 38 (66%) studies reported a positive association between wildfire smoke exposure and increased healthcare needs for cardiovascular disease.

"The body is not particularly good at eliminating [PM2.5 particles]."

IN A BUBBLE

The United Nations uses a source called IQAir. That link will take you to the world's major cities, ranked by worst air quality, according to the US Air Quality Index (US AQI). IQAir has a number of partners, including the United Nations Environment Programme, and the United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

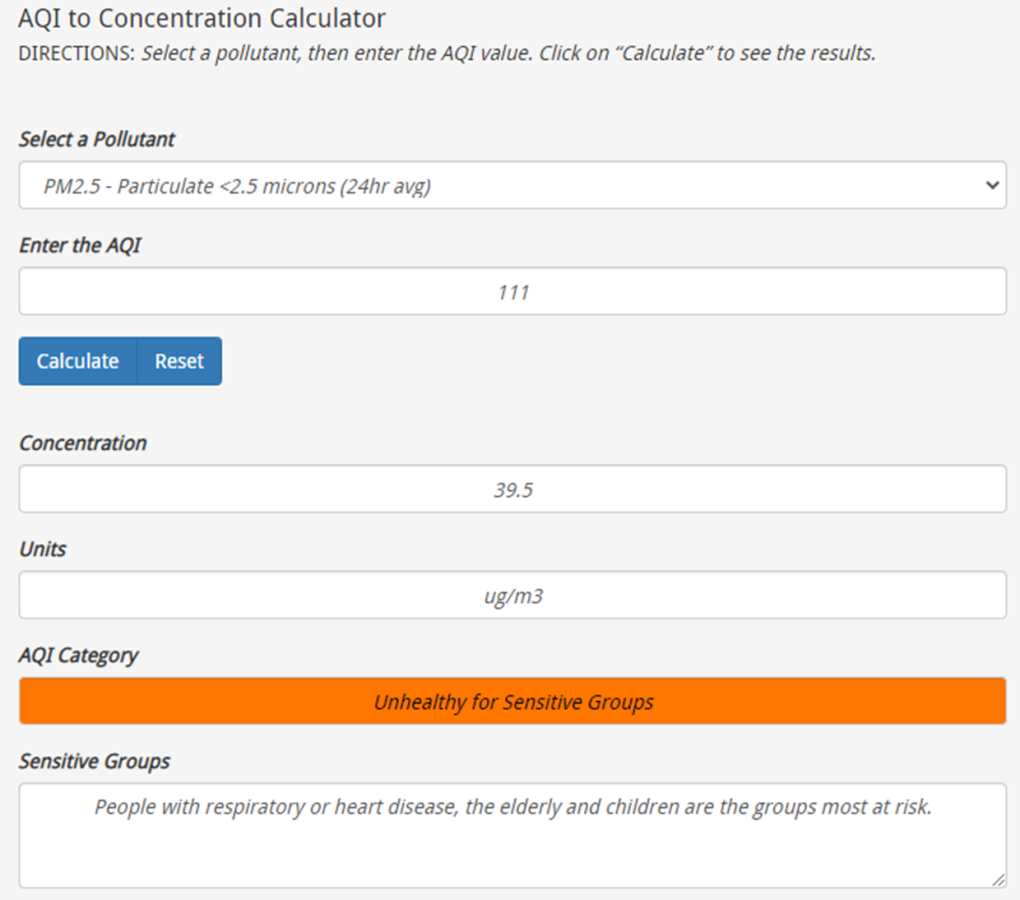

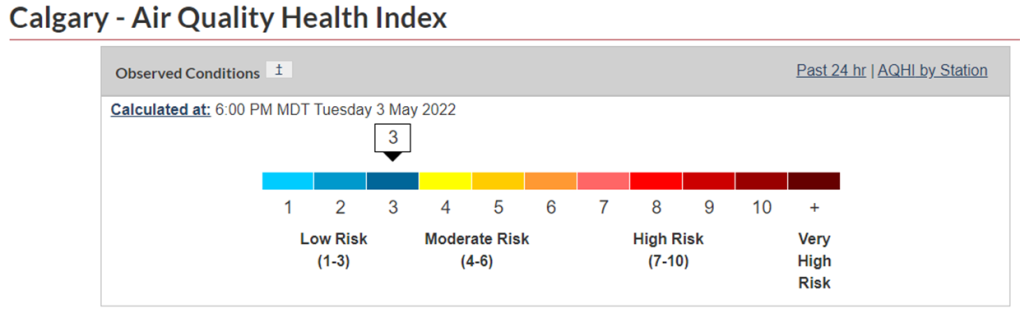

There's also a Canada page here; on the afternoon of May 3, Edmonton is at a 111 US AQI; this equated to an Air Quality Health Index rating of 4; a moderate risk.

AirNow.gov has a calculator on it to determine this, as well; just shy of 40 μg/m³ (microns per metre cubed):

Lastly, there's the 2021 report page, which found that "only three per cent of cities and no single country met the World Health Organization's PM2.5 annual air quality guideline." Globally, we remain a long way off from a passing grade.

Henderson notes that living in polluted environments year-round make for a "higher risk of developing chronic disease, and your life expectancy is maybe two to three years less than the life expectancy of somebody who isn't exposed to that type of pollution day in and day out." For those curious: here's the list of the worst-polluted cities of 2021.

Canada's most polluted city in 2021? Savona, B.C., near Kamloops.

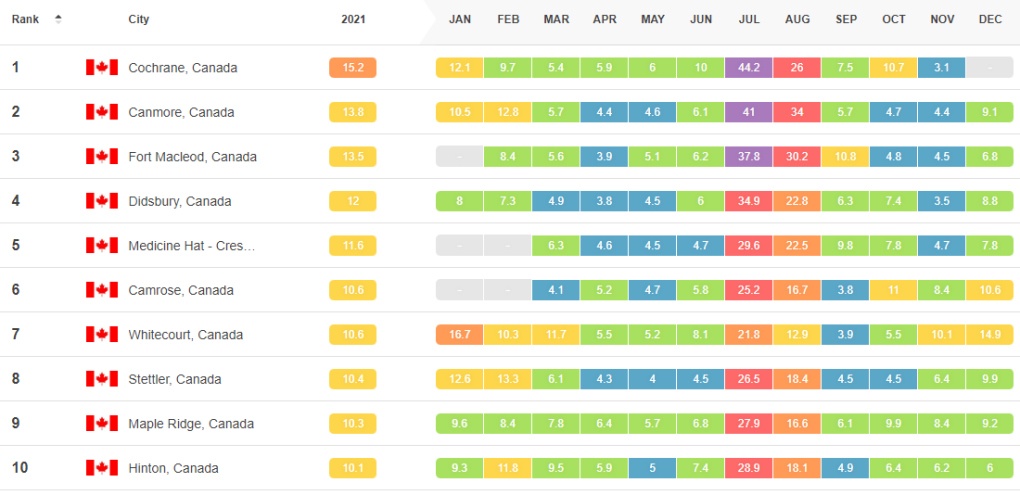

How about Alberta's? (Sorry, Cochrane!)

Note the way the data is skewed; air quality was terrible through July and August as a result of wildfire smoke, but otherwise, we were fine. We don't suffer from year-round pollution. This is also true of Savona, BC; the wildfires were the culprit for a tough couple of months.

A helicopter carrying a water bucket flies past the Lytton Creek wildfire burning in the mountains near Lytton, B.C., on Sunday, August 15, 2021. (file)

A helicopter carrying a water bucket flies past the Lytton Creek wildfire burning in the mountains near Lytton, B.C., on Sunday, August 15, 2021. (file)

The above data is based on the concentration of PM2.5 particles per square metre. An average of 44.2 μg/m³ in Cochrane through July, 2021 isn't far off from where Edmonton was on May 3, 2022; that's an average Air Quality Health Index rating of 4 throughout the month. Things improved, on average, in August.

Our takeaway: Canadians have a microcosm of a year-round effect. Even through our worst months, wildfire isn't prevalent all the time: "It's variable; one day, it's 10 microns per metre cubed of PM2.5. Another day, it's 250. The next day is 70. It jumps around all over the place," Henderson says. "And then it's winter again. And the air quality goes back to its normal, excellent conditions."

We have discussed rhesus monkeys and the generational effects therein; how are humans faring with prolonged exposure?

It's a young science; to look at longer-term effects, Henderson says "we have to look back 30 years; [but] the wildfire regime 20 years ago was just really different from what it is [today].

"Scientists all over the world are turning their attention to this form of pollution, to understanding exposures and their health effects. We're going to learn so much in the next five to 10 years. It's super exciting for someone like me, who's been in the game for a long time and is really happy to see this change.

"I don't know what we're going to learn, but we're going to learn a lot. In another five years, I'd be able to give you a much better overview of what the health effects actually are, what the risks actually are. As a public health practitioner, we need that so we can best guide people toward protecting their health."

OUR INDEX

Canada's Air Quality Health Index is designed with health protection in mind. Celine Audette, policy lead for the Air Quality Health Index as part of the Meteorological Service of Canada, explains why the shift was made.

"Before we had the Air Quality Health Index (AQHI), we just had the Air Quality Index. It didn't have health messaging associated with it. [The AQHI] was designed so people could just look at one number and know whether or not their health is at risk, and they can decide by that number what actions they will take."

The Air Quality Health Index section on the Government of Canada's website is exceptional and expansive for those wanting to learn more; all Environment Canada weather pages with access to air quality information will have it featured just above the seven-day forecast.

HOW ARE CANADIANS DOING?

"One-in-three Canadians are aware of the AQHI, we have a good response from Canadians," explained Audette. "It's become more available, and we have media partners that report on it. Wildfire smoke has become more prevalent."

Audette adds it's a mixed feeling when, as we had last year, wildfire smoke from western Canada reached New Brunswick. "We have success, [but it's] because the air pollution is bad. People care about their health, especially if they are at risk."

There were a few days this past summer where the index had Calgary in a very high spot. I asked Audette: on particularly dangerous days, why are air quality statements still just… statements?

The answer comes back to Aesop's fable, The Boy Who Cried Wolf, and culminates with everything Jack Chen, Paul Makar, and Chris Rodell said in Part One. It's also what Sarah Henderson said about the day-to-day shifts: Audette replied simply, "It's hard to predict where the smoke is going to be."

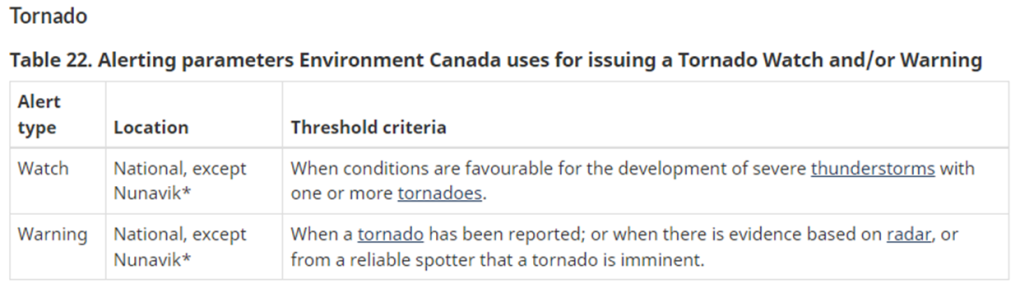

There's more to it than that, but first, a pivot to Environment Canada's warning criteria. Specifically, the watch and warning criteria for tornadoes:

Evidence is key, but reliable spotters even more so. Confirmation when a tornado touches down needs to border on irrefutable before a warning is issued. Public trust depends on it.

The same holds true for air quality. If our values are fluctuating rapidly and we bounce in and out of air quality warnings, "it's more of a mental health issue and making sure that people are not over-advised of what's coming," Audette says. "It increases stress. We want people to be prepared, but we don't want to over-advise them and cause alarms that weren't necessary in the first place."

'Gaps in data' is a running theme – as the science continues to evolve, these gaps narrow. Audette notes that Alberta and BC are in a better place, and that community PM2.5 sensing continues to advance. In fact, adding to their already-robust Environmental Monitoring information pages, an air quality map launched not long ago:

I closed by asking every member of the panels between both articles: What should the average Canadian do, or be aware of? What can we do, and how can we best prepare?

Sarah Henderson summarizes: "We often see that the indoor concentrations of PM2.5 in the average home without any type of air cleaning in place are about 60% of the outdoor concentrations. Staying inside can be protective if you are actively working to keep smoke out of the indoor environment and to clean smoke out of the indoor environment.

"The health effects associated with wildfire smoke, be they immediate and acute, or chronic and long-term, are from breathing wildfire smoke. The more you can do to reduce how much smoke you breathe, the more you will protect your health."

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

NEW Federal Liberals to pick new leader on March 9 as rules for leadership race are defined

The Liberal Party of Canada have announced leadership race rules late Thursday, including a significant increase in entrance fees and a requirement for voters to be Canadian citizens.

Liberals will remove 'fraudulent' memberships, as some register their pets to vote

A federal Liberal spokesman says the party can and will remove "fraudulent profiles" from its list of electors eligible to vote for its next leader.

NEW Why four Canadians traded their traditional office space for a life on the road

CTVNews.ca asked Canadians who've embraced the digital nomad lifestyle, or have done so in the past, to share their stories — the challenges, triumphs and everything in between.

New L.A.-area fire prompts more evacuations while over 10,000 structures lost to the 2 biggest blazes

The two biggest wildfires ravaging the Los Angeles area have burned at least 10,000 homes, buildings and other structures, officials said Thursday as they urged more people to heed evacuation orders after a new blaze ignited and quickly grew.

NEW Five ways homeowners can protect themselves from contractor fraud

Building or renovating a home can be one of the biggest expenses of one's life. It's costly, and potentially even more expensive if something goes wrong. Between 2022-24, the Better Business Bureau (BBB) received hundreds of complaints about general contractors in Canada.

Is the Hollywood sign on fire?

As fires scorch Los Angeles, fake images and videos of a burning Hollywood sign have circulated on social media.

How to improve climate predictions? McGill researchers turn to 19th century letters

A team led by McGill University researchers came up with a method they hope could improve climate models over Africa by combining them with 19th century missionary records, refashioning dubious documents in a bid to better inform projections of global warming's impact.

Ex-Trump adviser says Canada in 'difficult position' amid tariff threat, Trudeau resignation

In the face of a potential tariff war, U.S. president-elect Donald Trump's former national security adviser John Bolton says 'Canada is in a difficult position' in part due to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's resignation and a looming general election.

Canadian travellers now require an ETA to enter U.K. Here's what to know

Starting Jan. 8, Canadians visiting the U.K. for short trips will need to secure an Electronic Travel Authorization (ETA) before boarding their flight, according to regulations set out by the U.K. government.