Deaths of female grizzly, 3 cubs a reminder of population fragility, says wildlife scientist

Wildlife scientist Clayton Lamb puts a collar on bear EVGF97 in Elk Valley B.C. in 2019. The bear was killed by a train along with three of her cubs. (Courtesy Clayton Lamb)

Wildlife scientist Clayton Lamb puts a collar on bear EVGF97 in Elk Valley B.C. in 2019. The bear was killed by a train along with three of her cubs. (Courtesy Clayton Lamb)

The deaths of a female grizzly bear and her three cubs when they were hit by a train east of Elko, B.C. should serve as a wakeup call and another sad reminder of how fragile the powerful creatures' population is in that area, says the wildlife scientist who discovered their remains.

- Warning: details and images in this story may be upsetting to some readers

Clayton Lamb, a wildlife scientist at the University of British Columbia, tagged the female bear in September 2019 and had been tracking her since, along with a number of other grizzlies in southeast B.C.

"We called this bear EVGF97 (Elk Valley Grizzly Female No. 97). In 2019 she was approximately 11 years old, weighed 153 kilograms, and did not have cubs with her," he said about the tagging two years ago.

"She was in very good body condition, with 36 per cent body fat. Unlike us, bears are actually striving to be as fat as possible, so she was winning at that. She was one of the heaviest and fattest females in our study."

After getting a mortality signal from the mother's collar in early October, Lamb discovered the remains of the three cubs below a train bridge over a riverbed in the Elk Valley region of B.C., and the mother was found a few hundreds metres down the tracks.

They had been hit by a CP Rail train, and the collision was reported to authorities.

The female didn't have cubs with her when researchers did a check in 2020, but she was spotted with a male at the time. The three cubs were born this spring, making her the first to produce that many offspring at once.

"Although not entirely uncommon, this was the first observation of a female with three offspring in over 100 animal-years of monitoring the reproduction of ~30 female bears in the Elk Valley," said Lamb.

The remains of three grizzly bear cubs, which were killed when they were hit by a train. (Courtesy Clayton Lamb)

The remains of three grizzly bear cubs, which were killed when they were hit by a train. (Courtesy Clayton Lamb)

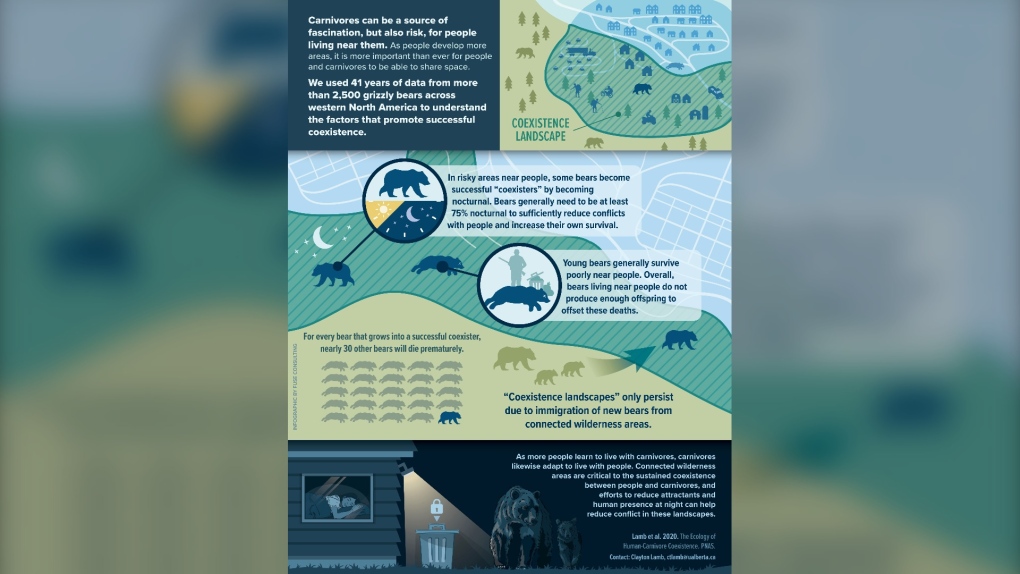

Bear ecology in the Elk Valley, and many other areas of grizzly habitat in Western Canada, requires a balancing act between people and animals.

"It is a busy place with towns, highways, railways, mining, logging, and lots of recreation. It supports a high density grizzly bear population that lives amongst a bustling human-dominated valley," said Lamb.

"The high density of bears is supported by productive habitat in the valley, and from an influx of bears from adjacent areas that are more wild."

Lamb figures the bears were feeding or moving through the area when they were spooked by the train and ran onto the bridge.

"I think they panicked and they ran along the rail and onto the bridge, I don't think they were crossing the bridge," he said. "The land below the bridge is a really nice easy, kind of gravel bed, it wouldn't be particularly hard to cross. I do think they got pushed onto there and turned and faced the train and it didn't work out."

Lamb's research has shown grizzly bear populations near people often have more animals die each year than are born, making the loss of three cubs — two females and a male — especially hard hitting.

"Obviously this begs the question of how they persist, and what we find is that bears from more remote, secure areas disperse into these areas and replace the bears that are dying at high rates," he said.

"It’s a bit paradoxical because dispersing animals from wild areas are key to sustaining front country bear populations, yet clearly these dispersing animals are moving to much more dangerous place than they left. So these dispersing individuals help support coexistence landscapes yet may doom themselves to a premature death.

"The female and her cubs killed by the train are now unfortunately part of this mortality trap dynamic. Losing an adult female is never good for bear populations, and the two female cubs she had makes this loss even more concerning. Unfortunately high mortality rates of bears is an issue we have been grappling with in the Elk Valley for some time."

Collisions with trains and vehicles account for about a third of grizzly bear deaths, says Lamb.

"These collisions are not good for bears or people. Some solutions exist, such as fencing highways and building wildlife crossing structures, as some folks may have seen along Highway 1 in Banff," he said.

"Reducing railway collisions is trickier, but innovative solutions exist, such as early warning systems that can alert animals to an oncoming train and help them get out of the way faster. We don’t want to always rely on animals dispersing from elsewhere to make the Elk Valley grizzly bear population viable. A larger goal is reduce mortality to a point where the bears can sustain themselves."

Lamb says he hopes the deaths spark a further desire to find solutions "to help make this landscape work better for people and wildlife alike."

"Currently a lot of the infrastructure and research focused on helping wildlife cross transportation corridors is focused on national parks, such as Banff, but we know that there are many areas outside parks where grizzly bears and other important species such as elk, moose, sheep, and deer, are hit much more frequently."

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

WATCH LIVE The world begins welcoming 2025 with light shows, embraces and ice plunges

From Sydney to Vladivostok to Mumbai, communities around the world have begun welcoming 2025 with spectacular light shows, embraces and ice plunges.

Poilievre's Conservatives end 2024 hitting long-term high in the polls amid Trudeau resignation calls: Nanos

Pierre Poilievre's Conservatives are closing out 2024 hitting a new long-term high in ballot support, with a 26 point advantage over the Liberals amid calls for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to resign.

BREAKING Female victim in Calgary double homicide identified as elementary school teacher

Rocky View School Division (RVSD) on Tuesday identified the woman who was murdered Sunday night in Calgary as Ania Kaminski, an elementary school teacher in Cochrane, west of the city.

One charged following terrifying road rage incident on Hwy. 11 in northern Ont.

Ontario Provincial Police are asking for the public's help in investigating a road rage incident Monday on Highway 11 near Temiskaming Shores.

Telegraph Cove, B.C., fire takes out beloved businesses, parts of boardwalk

The most iconic portion of a picturesque boardwalk in Telegraph Cove, B.C. was destroyed by fire on Tuesday morning.

Woman burned to death inside New York City subway is identified

The woman who died after being set on fire in a New York subway train earlier this month was a 57-year-old from New Jersey, New York City police announced Tuesday.

Xi says no one can stop China's 'reunification' with Taiwan

No one can stop China's "reunification" with Taiwan, Chinese President Xi Jinping said in his New Year's speech on Tuesday, laying down a clear warning to what Beijing regards as pro-independence forces within and outside of the island of 23 million people.

WATCH A jet carrying the Gonzaga men's basketball team ordered to stop to avoid collision at LAX

The Federal Aviation Administration has launched an investigation after a private jet carrying the Gonzaga University men's basketball team nearly crossed a runway as another flight was taking off Friday at Los Angeles International Airport.

Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt reach divorce settlement after 8 years

Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt have reached a divorce settlement, ending one of the longest and most contentious divorces in Hollywood history but not every legal issue between the two.