CALGARY -- ED.NOTE: This week, the federal government introduced legislation to create a review process for wrongful convictions. They called it 'Milgaard's Law' after David Milgaard, who spent 23 years in prison for a crime he didn't commit. Prior to his death in 2022, Milgaard spoke to CTV News reporter Kevin Green for a January 2020 article. Here it is.

It was January 1969 when Saskatoon police discovered the body of nursing student Gail Miller in a snowbank.

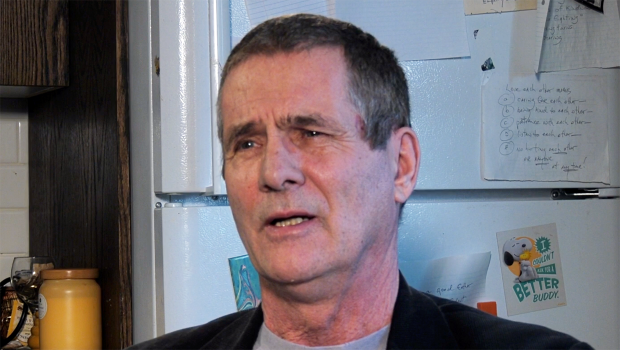

At the same time a carefree teen named David Milgaard was on a road trip with friends, passing through Saskatoon.

Under tremendous pressure to solve the case, Saskatoon police focused their attention on Milgaard.

In May 1969, with a warrant issued for his arrest, Milgaard turned himself in to the RCMP in Prince George.

“I said well sure, I didn't do anything. I had no real concern to do it.” says Milgaard. “I didn't feel very uncomfortable.I'm just glad that I was trying to help.”

Flash forward to January 31, 1970. Millgaard was in court, listening as a jury pronounced him guilty of the murder he knew he hadn’t committed.

“There isn't anything I think worse in my life than how I felt when they came out with my verdict of being guilty of that terrible crime,” says Milgaard, looking back on the day 50 years ago. “I heard this great big body moan behind me, and I turned around and I saw my father looking so weak and I just got terrified.

"And I think that was the worst moment I ever spent in my life.”

It turns out that in the year between Miller’s murder and Milgaard’s’s conviction, two of Milgaard’s friends friends, Nicole John and Ron Wilson changed their statements: they had originally provided police with information that originally placed Milgaard away from the scene of the crime.

When the case came to trial, they had altered their stories.

“I I just was overwhelmed. I couldn't understand why (they changed their statements),” says Milgaard.

“I mean, they both knew the truth.”

Forgiven friends, but not system

In the half century since Milgaard says he understands the pressure his friends were placed under by a police force desperate for a conviction. He says he’s forgiven them both.

“She (Nicole John) was kept inside a jail cell until she did what they wanted her to do," he says. "He (Wilson) was told that he was going to probably be charged with the murder if he didn't do what they wanted him to do. “

But Milgaard cannot forgive the system he says says forced them to lie in court.

'Will you stop typing?'

For over two decades Milgaard languished in prison, spending his time inside crafting letters to anyone he thought might help reopen his case.

“Somehow or other I got a typewriter," he says. "And I was sitting there and I was trying to type letters to tell the whole world I'm not guilty.”

“Every once in a while I’d hear someone yell at me ‘Will you stop typing?" he says. "Stop using the typewriter, you know, dummy up, stop making the typewriter noise.’”

Milgaard continued to maintain his innocence even when told admitting to the crime would shorten his stay in prison.

Meanwhile, outside prison his mother Joyce waged an unrelenting campaign to see her son set free, including a public confrontation with Conservative justice minister, and future prime minister Kim Campbell.

”When she ran away from my mother, who's trying to say I need you to take a look at some material, it really galvanized a lot of the mothers in Canada.” says Milgaard. “They said ‘well, that's not right.’ And you know, it kind of helped us more than that it hurt us.”

Released but not redeemed

In 1992, the Supreme Court of Canada reviewed Milgaard’s case, ruling the government of Saskatchewan should set aside the conviction. Saskatchewan refused, instead issuing a stay of his charge. A stayed charge is not the same as a declaration of innocence.

“You know, it was the worst possible thing that they could do to a wrongfully convicted person.” says MiIlgaard. ” You know (you're innocent of the charge), and you're right, you know, the public (was thinking) Is he guilty? Isn't he guilty? I hated them for doing that to me."

Joyce Milgaard was also unsatisfied with her son's release without redemption, and continued pressing the case.

On July 18, 1997, a DNA test from a lab in England showed the semen samples on Gail Miller’s clothing were not Milgaard’s, essentially clearing him of the crime. Exactly a week later serial rapist Larry Fisher was arrested, and charged with the 1969 rape and murder. In the period that Milgaard was serving the sentence for the murder Fisher had actually committed, Fisher had sexually violently assaulted at least 23 other women.

“That hits upon the most important issue about wrongful convictions in this country. “says Milgaard. “You know, when they are putting people inside prisons for wrongful convictions, there are people outside prisons that continue to do these horrendous things to other people."

Saskatchewan apologizes with $10 million

Only after the DNA exoneration did the Saskatchewan government apologize for Milgaard’s conviction. In 1999, Saskatchewan reached a $10 million settlement with Milgaard.

Finally free from prison, and from the conviction, Milgaard made up for his lost time by travelling the world, logging close to 40 countries’ stamps in his passport, before the burst of the dot-com bubble in 2000 wiped out most of the money he had left from his settlement.

Today he lives in a modest townhouse in Cochrane with his 14-year-old son and 11-year-old daughter. The 67-year-old spends much of his day at his kitchen table, which is piled high with letters from current prisoners asking for help in their bids for release.

They have Milgaard's sympathy.

“One of the strongest indicators of a wrongful conviction is the fact that for years and years and years, people maintain their innocence.” says Milgaard. “ It's the strongest indicator that in fact, they are telling the truth.”

Despite advances in forensic science, legal experts say wrongful convictions continue to be a regular occurence.

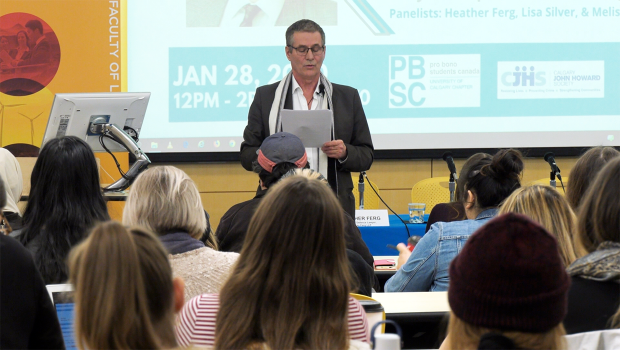

“There are wrongful convictions that happen I would say every day.” says University of Calgary law professor Lisa Silver. “When I read case law, every day there is inevitably an appeal allowed on a miscarriage of justice.“

Righting wrongful convictions

In his mandate letter to federal justice minister David Lametti, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made dealing with wrongful convictions his top priority stating :

”I will expect you to work with your colleagues and through established legislative, regulatory and Cabinet processes to deliver on your top priorities. In particular, you will: Establish an independent Criminal Case Review Commission to make it easier and faster for potentially wrongfully convicted people to have their applications reviewed.”

This month Milgaard was appointed to a new federal Independent Review Board Working Group, set up to examine the best way to review claims of wrongful conviction.

He’s hopeful, --but skeptical -- it will lead to meaningful change.

How could he be anything but? Wrongful convictions aren't a legal theory, or a research paper, or a royal commission report for him.

They were three decades of his life.

“It's so important at some point, you know, we wake up and realize that what we're doing inside this criminal justice system is dead wrong," he says.

”Let's see," he adds, "if they will actually say that their motto is getting it done quickly, but doing it right.

"When they say that to me," David Milgaard says, "I will be satisfied.”