Calgary and Edmonton's low-income rental units disappearing: report

Rental properties are shown in Calgary, Alta., Tuesday, March 12, 2019. A report from the University of Calgary's School of Public Policy suggests governments need to pay attention to what drives the availability of low-income rental units, which have sharply dropped in both Calgary and Edmonton over the past 30 years. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jeff McIntosh)

Rental properties are shown in Calgary, Alta., Tuesday, March 12, 2019. A report from the University of Calgary's School of Public Policy suggests governments need to pay attention to what drives the availability of low-income rental units, which have sharply dropped in both Calgary and Edmonton over the past 30 years. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jeff McIntosh)

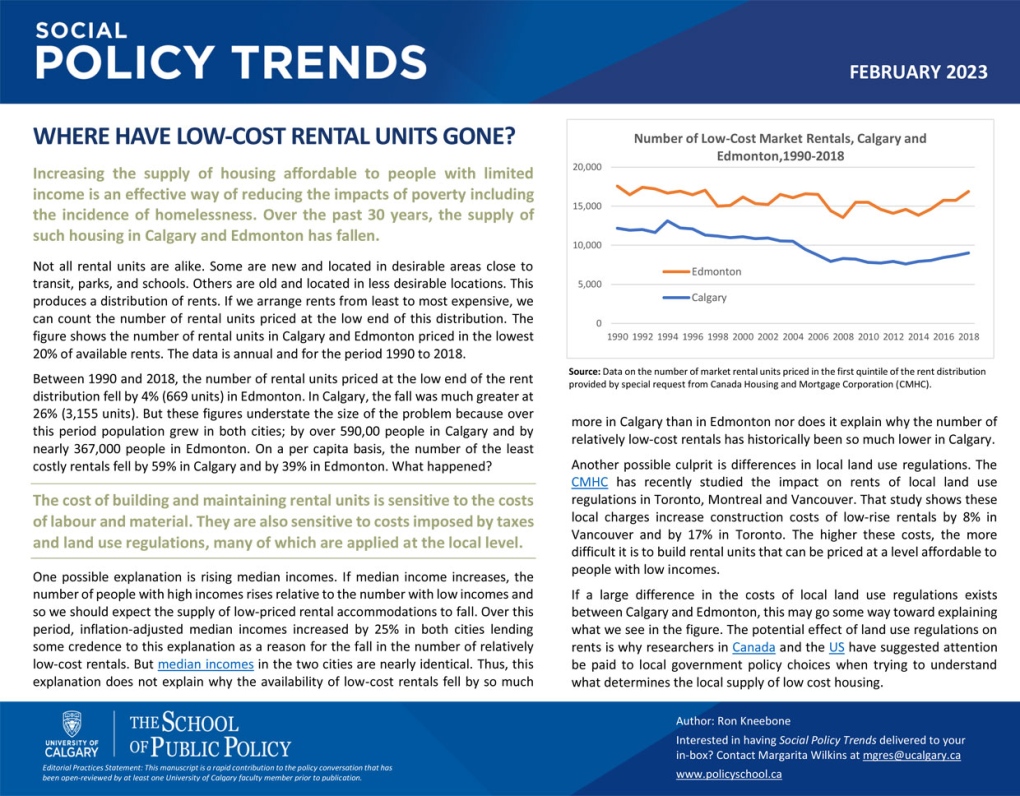

A new report suggests the number of low-income rentals available in both Calgary and Edmonton has sharply dropped over the past 30 years, highlighting another challenge facing Albertans seeking affordable housing.

The University of Calgary's School of Public Policy released the data in its Social Policy Trends report on Thursday.

In it, the U of C says between 1990 and 2018, the number of low-income rental homes dropped by four per cent (669 units) in Edmonton and by 26 per cent (3,155 units) in Calgary.

However, those figures on their own don't quite illustrate the extent of the problem, the school says.

"Over this period population grew in both cities; by more than 590,000 people in Calgary and by nearly 367,000 people in Edmonton," the U of C said. "On a per capita basis, the number of the least costly rentals fell by 59 per cent in Calgary and by 39 per cent in Edmonton."

The study says low-income rental units are defined as older buildings in less desirable locations that are further away from resources like transit, parks and schools.

Ron Kneebone, the author of the study, says one of the possible reasons behind the change could be a shift in median incomes.

"If median income increases, the number of people with high incomes rises relative to the number with low incomes and so we should expect the supply of low-priced rental accommodations to fall," he said in the report, adding that inflation-adjusted median incomes in both cities rose by 25 per cent over the period of time the study examined.

However, since the median incomes in both Calgary and Edmonton are nearly identical, Kneebone believes something else may be to blame for the decrease.

"This explanation does not explain why the availability of low-cost rentals fell by so much more in Calgary than in Edmonton nor does it explain why the number of relatively low-cost rentals has historically been so much lower in Calgary," Kneebone wrote.

He suggests local land-use regulations as well as the cost of building and maintaining rental units – particularly when it comes to labour and material costs – could also play into the issue.

"The CMHC has recently studied the impact on rents of local land use regulations in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver," he said.

"That study shows these local charges increase construction costs of low-rise rentals by eight per cent in Vancouver and by 17 per cent in Toronto. The higher these costs, the more difficult it is to build rental units that can be priced at a level affordable to people with low incomes."

If such a large difference in costs exists between Edmonton and Calgary, Kneebone suggests this may add weight to the argument researchers are trying to make with local governments.

"(It suggests) attention be paid to local government policy choices when trying to understand what determines the local supply of low-cost housing," he said.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Celine Dion delivers stirring comeback performance at Paris Olympics opening ceremony

Against the rainy Paris night sky, Celine Dion staged the comeback of her career with a powerful performance from the Eiffel Tower to open the Olympic Games.

Jasper wildfire: 'Several weeks' before residents can return, premier says

Premier Danielle Smith said Friday afternoon in Hinton while weather conditions are cooler, the Jasper fire is still considered out of control and that Jasper residents can expect to be away from their homes 'for several weeks.'

Missing 3-year-old boy found dead in creek in Mississauga, Ont.: police

A three-year-old boy has been found dead a day after he went missing in a park in Mississauga, Ont., Peel police say.

Irish museum pulls Sinead O'Connor waxwork after just one day due to backlash

An Irish museum will withdraw a waxwork of singer-songwriter Sinéad O'Connor just one day after installing it, following a backlash from her family and the public, it told CNN in a statement on Friday.

Winnipeg senior's account overdrawn for $146,000 water bill

A Winnipeg senior is getting soaked with a six-figure water bill.

FBI says Trump was indeed struck by bullet during assassination attempt

Nearly two weeks after Donald Trump’s near assassination, the FBI confirmed Friday that it was indeed a bullet that struck the former president’s ear, moving to clear up conflicting accounts about what caused the former U.S. president’s injuries after a gunman opened fire at a Pennsylvania rally.

Driver charged after flashing high beams at approaching police

Orillia OPP arrested and charged a driver with impaired driving after flashing their high beams.

Turpel-Lafond won't sue CBC over Cree heritage report that took 'heavy toll': lawyer

The lawyer for a former judge whose claims to be Cree were questioned in a CBC investigation says his client is not considering legal action against the broadcaster after the Law Society of British Columbia this week backed her claims of Indigenous heritage.

Major Canadian bank experiences direct deposit outage on payday

Scotiabank says it has fixed a technical issue that impacted direct deposits on Friday morning.