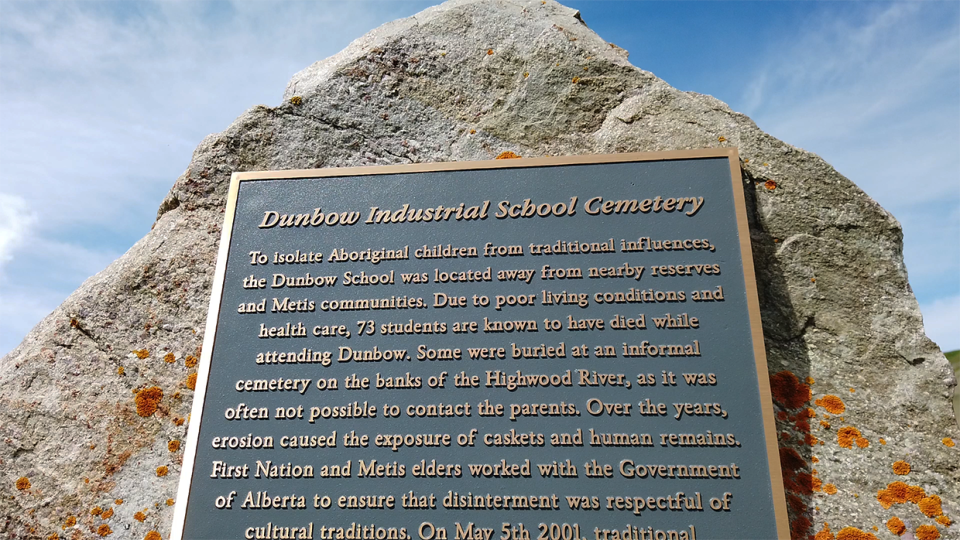

CALGARY -- The search continues to identify the bodies of children found buried near the former Dunbow Industrial School, south of Calgary, which operated from 1884 until 1922. To date, 34 children have been named, but dozens of other bodies are still missing.

Logs kept by school administrators, obtained by Jeanette Starlight from Missionary Oblates, offer a glimpse into the care – or lack thereof - the students received.

“Joseph Arcan 13/06/1888 Died at school, started cemetery (sic) – indicated in journal.”

Joseph Arcan was the first student to die while attending Dunbow Industrial School. Before the school was closed in 1922, 72 more students would also die.

“131 Charles Godin 12/04/1897. Died on the 12th of April after a very short Illness of Brain Fever – not seen by doctor before his death.”

The records also offer insight into how the Catholic priests and nuns running the school viewed the First Nation students brought there to live and study, and what they felt was the student's future, had they survived:

“024 Lucy Sinclair 17/08/1895This girl of the Blackfoot tribe was very well disposed. Learned English very quickly, she would have made a good servant girl. A diligent and neat worker. She suffered from a hip disease; fell into consumption from which she died.”

In total 430 students from First Nations across Alberta, attended Dunbow Industrial School . also known as St. Joseph's Industrial School during its 38 years of operation. Most were Siksika, or TsuuT'ina (known at the time as Blackfoot and Sarcee).

One in six died while attending the school, which was located along the banks of the Highwood River southeast of Calgary, near the end of what is now Dunbow Road.

Students who died at the school were buried in a cemetery near the river’s edge. In 1996 the flooding Highwood River eroded the banks. Caskets and bones spilled into the river and began washing away the remains.

“The hill was eroded very fast," said TsuuT’ina archivist Jeanette Starlight, who has been gathering information on Dunbow School since the 1996 gravesite exposure. “They put two to three bodies in one coffin, and then they buried them that way, so some of the remains that washed down to the river, they are probably still in the river.”

Documents she has collected show the children were stripped of their native clothing and made to wear western attire.

Each was assigned Christian names and given a number.

The remains of 34 of the students located and reinterred at a site several hundred metres away from the river. Today a rock monument and a stone cairn commemorate the site. On the fence around the graveyard hangs a tiny orange beaded shirt, along with teddy bears, and dreamcatchers.

A tiny pair of children’s shoes sits aside the gate to the site.

Looming in the background 200 metres away, on private land, and only accessible with the owners permission, are some of the remaining school buildings. They have begun rapidly collapsing in recent years. Inside the barn there is still tack hanging on the walls. You can see names painted on the wood and inscriptions citing religious events carved into door panels.

In 2014 a Strathcona-Tweedsmuir School (STS) Humanitarian Outreach Program honoured the 34 children whose bodies had been discovered.

Traditional aboriginal and Christian ceremonies were held to mark the reburial of children. Students participating released butterflies while calling out the names of the Dunbow School students who had been identified.

“For them that was very empowering that they had honoured these children. What was very impactful is that these children were their age, and that resonated with a lot of the children," said Judy Goldsworthy, an STS teacher who worked on the project. “ It's important for me that children know the vocabulary behind truth and reconciliation, and that they are personally able to honour our history, good and bad.”

The ceremony was captured in a short film titled “Little Moccasins” produced by Laurie Somerville and directed by Ken Matheson.

Matheson recalled the ceremony as one of the most impactful moments in his life “Through making the film I was able to see it through the kids eyes, without any preconceived prejudice,” said Matheson “ I think to make change, it will have to be generational change. You have to start with the children.”

Starlight says it’s likely some of the children’s remains will never be found, but she hopes the monuments at the grave site offer some solace, and healing for the families, and for the spirits of the children buried there.

“I don't do this for myself. I do this for the children," she said. "Their spirits should be now at peace. They have to be at peace. That's the only thing that I really, really want."

“I believe that these remains, any remains can find the peace, and see a better world, and be with their parents," said Starlight. "They were taken away so young and now they want their parents. That's all I want. To find peace.”